By Adriana Maldonado

This text is an edited (brief) version of my dissertation for the MA Traditions of Yoga and Meditation at SOAS University in London. © Adriana Maldonado, N8 Yoga 2021. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Adriana Maldonado with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Contents

WHAT IS ATTENTIONAL CONTROL OR CONCENTRATION?. 1

WHAT ARE TRANCE AND THE YOGIC EXPERIENCE?. 2

A REVIEW OF NOTIONS AND TECHNIQUES OF AC IN ANCIENT YOGA TEXTS. 4

THE HAṬHAYOGA TREATISES GHERAṆḌASAṀHITĀ AND VIVEKAMĀRTAṆḌA. 8

ATTENTIONAL CONTROL AND THE KEY GURUS/FIGURES FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF MPY. 11

STEADINESS OF MIND AND TRANCE THROUGH ĀSANA. 17

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND REFERENCES. 24

Introduction

Different techniques of concentration in yoga can lead to experiences of trance. These experiences, understood as Altered States of Consciousness (ASCs) prove beneficial for wellbeing. This text will explain why this is the case.

What is trance? What are the techniques used to enter trance states within the history of yoga? What techniques of concentration were and are taught by popular teachers and Gurus of Yoga? How could we define the experience of wellbeing after a yoga practice? And are people experiencing trance states in a contemporary studio setting? I explore the answers to all these questions and argue that concentration or Attentional Control -as is commonly used in psychology- whether on external factors and related to perception, or on internal factors -visualization, thoughts, or other mental processes- and on the path of yoga meditation, has remained a constant feature of yoga – from its first definitions as a set of techniques and practices to attain liberation, through to our modern day understanding of yoga to support mental and physical health.

In recent years, several research studies have demonstrated that yoga promotes wellbeing[1]. National Health institutions such as the NHS in the UK use yoga as complementary treatment in healthcare, and scholars, teachers and practitioners seem to agree that yoga has a transformative nature that can support wellbeing. But descriptions and propositions of yoga practices remain diverse – from the beginning of its history to modern day. Particularly, Modern Postural Yoga (MPY[2]) in itself, is a spectrum of propositions that can range from very physical-athletic to relaxing nearly static practices. Nevertheless, mind work through concentration, such as fixation on certain places in the body -e.g., gazing in between the eyebrows- and focus on breath, have been constants in nearly all propositions.

Concentration leads to absorption; this is understood as a state of trance or Altered State of Consciousness (ASC). Meditation and the state of flow are states of trance or ASCs -all these concepts will be discussed below I will demonstrate that while there are differences between absorption in deep states of meditation in seated postures, and absorption induced by āsana and vinyāsa, both are trance experiences and prove beneficial for wellbeing.

WHAT IS ATTENTIONAL CONTROL OR CONCENTRATION?

Attentional Control (AC) or concentration[3] refers to our ability to choose where we direct our attention and what we ignore. AC is initially driven by stimuli, but as the practitioner acquires more experience it can shift to a goal-directed concentration as distracters disappear. Research demonstrates that AC improves with regular practice; this involves the processes of learning and memory.

According to Tart (2000), attention and awareness conform the ‘major energy of the mind’; he describes this energy as our ability to do work or to make something happen, a ‘psychological energy.’ AC as energy is at the heart of yoga practices, for example concentration on breath awareness and on different parts of the body or on objects of meditation such as mantras, physical sensations, images, and gazing points.

In the context of yoga history and philosophy, the mind must be kept focused without distractions to advance towards the goal of yoga that has to do with understanding the nature of the Self. AC techniques are usually involved whether this goal is related to achieving Samādhī, described as a state of trance in the path of salvation, or to support wellbeing in a modern context.

WHAT ARE TRANCE AND THE YOGIC EXPERIENCE?

The Cambridge dictionary defines trance as ‘a temporary mental condition in which someone is not completely conscious of and/or not in control of himself or herself.’ Castillo (1995) notes that trance is a ‘human behaviour’ that can be induced by focusing attention and that is present in all cultures and manifested in different ways. It usually involves processes that bring a person from her ‘everyday consciousness’ into a different mental state and then back to their normal but somehow ‘changed by the experience’ (Harrington 2016).

The study of trance is surrounded by controversy and confusion as it was typically related to shamanism, spirit possession, and often considered a pathology. Although this is true, these are all trance experiences and trance could be a sign of a pathology,

The ability of experiencing trance or Altered States of Consciousness[4] (ASC) is universal but may be shaped by the context and what induces that trance. Trance can be induced by practicing sports, performing music, dancing, or any activity that requires concentration; in addition, external awareness can continue in light trances, occurring alongside ‘ordinary consciousness’ (Inglis 1990).

Trance plays a role in most religions; and it is related to mystic or ecstatic experiences. Tart (2000) argues these ‘mystic experiences have formed the underpinnings of all great religious systems.’

Experiences of ecstatic trance, as Inglis (1990) argues, often give a sensation of ‘the oneness of everything’, people afterwards feel transformed and connected to nature and their surroundings, or as in the above example connected to God.

Many religious traditions, including yoga traditions, had as a goal the cultivation of trance with a view to attaining ecstasy (Inglis 1990). This involves focusing on an object of concentration in a process of emptying the mind except the perception of the object in question (Inglis 1990).

Trance states, as pointed out by Connolly (2014) can be light or deep; and they differ in their orientation, they can be internally focused or externally focused. They can be self-induced, group-induced as part of a collective practice, or induced by another person, for example as in hypnosis. In addition, the environment and atmosphere during practice can induce the sense of calmness, as well as practicing in a social context; as Nevrin (in Singleton and Byrne 2008) argues, practicing in a group can ‘unload the burden of individuality’; in a group, the practitioner could experience the sense of belonging to something larger transcending his own self (Malbon 1999).

Persuading the mind is relevant to access concentration, as well as regular practice and faith, belief or confidence in the practice.

The Yogic Experience is a state of trance, light or deep, and as Connolly (2014) points out has to do with displacing or inhibiting conscious mind processes. The method used to induce this trance affects the experience of trance (Connolly 2014), and the experience of trance states, usually has the effect of feeling ‘joyful’ (Tart 2000).

A REVIEW OF NOTIONS AND TECHNIQUES OF AC IN ANCIENT YOGA TEXTS

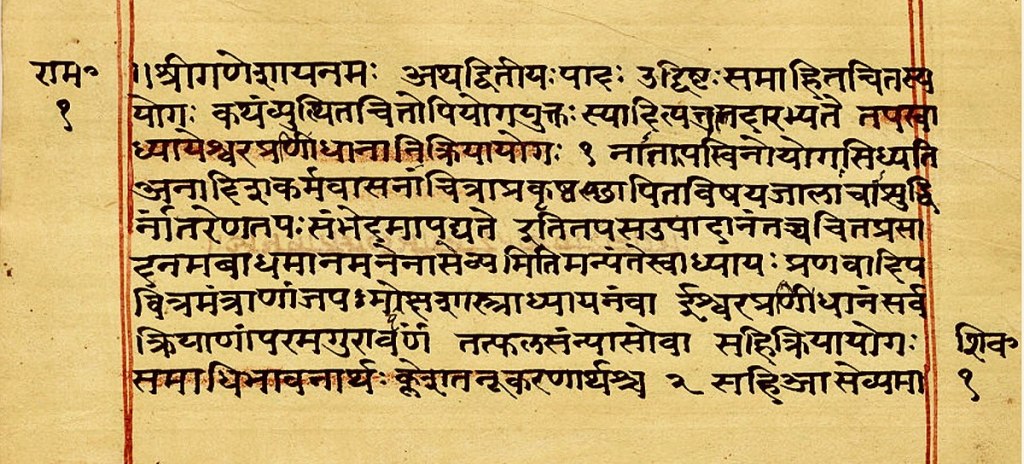

Because Yoga texts are countless, covering a long history of more than twenty centuries, I will focus on only a few that in my mind are a good example of the sources where many concepts, techniques and principles of yoga were originally presented. I briefly mention the Kaṭha Upaniṣad, the Bhagavadgītā, and a bit more in depth the Pātañjalayogaśāstra and a couple of haṭhayoga treatises.

According to Mallinson and Singleton (2017) the below excerpt of the Kaṭha Upaniṣad is the ‘earliest known definition of yoga’, dated to the 3rd century BCE. Here we find a clear example of the importance of mind control as a root of yoga.

When the five perceptions are stilled

Together with the mind,

And not even reason bestirs itself;

They call it the highest state.

When senses are firmly reined in,

That is Yoga, so people think.

From distractions a man is then free,

For Yoga is the coming-into-being,

As well as the ceasing-to-be.

Kaṭha Upaniṣad 6:10-11 (Olivelle, 1996:246).

Similarly, in the Bhagavadgītā, part of the Mahābhārata dated to the 3rd century CE yoga is very much the bringing of the mind into focus:

‘12

when one directs the mind

to a single point,

actions of the senses

and thoughts controlled,

sitting oneself on the seat,

one should join to yoga

in order to purify

the self.

13

One is firm

unmoving,

holding in balance

the head, neck and body,

looking at the tip

of one’s own nose,

not looking in any direction.

Bhagavadgītā, 6.12-13 (Patton 2008:73)

The above verses suggest a process of concentration through AC techniques, e.g. gazing points, to induce a meditative trance. The verses that follow the above (see Patton 2008) explain that yoga is also about bringing concentration to all aspects of life, allowing the practitioner to experience joy.

Along the history of yoga, focusing on the space between the eyebrows to access concentration, seems the most used AC technique from early CE to current contemporary practices.

THE PĀTAÑJALAYOGAŚĀSTRA

Dated circa the 4th century CE (Mallinson and Singleton 2017), the Pātañjalayogaśāstra is understood as the Yoga Sūtra (YS) of Patañjali and Vyāsa’s commentary, known as the Yogabhāṣya.

Patañjali’s system is a progressive path involving concentration and breath work to bypass the ‘turnings of thought’ entirely by restraining bodily actions and stabilising the mind (White 2014). The ultimate goal is the end of suffering, liberation or the realisation of the Self.

Yogaś citta-vṛtti-nirodhaḥ

‘Yoga is the stilling of the changing states of the mind.’

Yoga Sūtra of Patañjali I.2(translated by Bryant 2009:10)

Edwin Bryant (2009) argues that if the term yoga here in the above sūtra is to mean ‘yoke’ this ‘entails yoking the mind on an object of concentration without deviation’.Bryant translates cittavṛtti as ‘changing states of the mind’ while Feuerstein (1989:26) translates it as ‘fluctuations of consciousness’. Feuerstein may be touching on the transition from a normal state of consciousness to an ASC through AC techniques, the accessing to a trance state.

AC is presented by Patañjali as Dhāraṇā: ‘the binding of consciousness to a [single] spot’ (Feurstein 1979). Feurstein argues that one-pointedness or Ekāgratā ‘is the underlying process of the technique of concentration.’ This technique allows the practitioner to attain a state of trance.

This yogic trance experience is described as sāttvic, ‘free from pain and luminous’, and ‘free from rajas and tamas’ that are the sources of pain and obscuration (Bryant 2009).

The heavy use of the Pātañjalayogaśāstra in modern discourses of yoga may be linked to later 20th century promoters of the practice such as Kṛṣṇamācārya, whose work I explore later in this text.

THE HAṬHAYOGA TREATISES GHERAṆḌASAṀHITĀ AND VIVEKAMĀRTAṆḌA

Fixation, visualisation and breath control are all AC techniques that lead to absorption or trance and are key for the Gheraṇḍasaṁhitā and for the Vivekamārtaṇḍa. The texts describe complex techniques to bring the practitioner’s mind into focus and access states of yogic trance, both in seated meditation and while performing āsana, prāṇāyāma, and mudrā. The teaching of the Gheraṇḍasaṁhitā, as of many other yoga texts, is that the deeper the state of trance through the fixation of the mind, the closer the practitioner is to achieving the goal of yoga, i.e., Samādhī.

In chapter 2 (see Mallinson 2004) there is the description of siddhāsana (seated posture): ‘remain motionless with the sense organs restrained while staring between the eyebrows.’ This is similar to the description of Śāmbhavī mudrā, mentioned in chapter 3,which is a goal-oriented meditation, ‘seeing the bindu that consists of Brahman’, and which also involves the gazing point in between the eyebrows. Bindu, although can have different meanings, can refer to a point on the body (Mallinson 2007).

Another method described to induce trance through fixation is the ‘five dhāraṇā’. These are fixations of ‘breath and mind’ (Mallinson 2004), on the different elements and on different areas of the body, as per indicated in the text, for two hours each. Feuerstein (2008:396) points out that these concentration practices are included in the chapter of mudrās. This, he argues, demonstrates ‘the close relationship that exists in Yoga between physical practice and mental focus’.

Similarly, in the Vivekamārtaṇḍa there is extensive description of breathing, gazing practices and specific concentrations or fixations such as focusing on cakras to induce absorption:

(160) Absorption is when the mind and the self of the yogi become one like salt mixing with water.

(162) Absorption is when the individual self and the supreme self become one, and all conceptions are destroyed.

(163) For in this teaching the activity of the mind in the sense organs is a different process. When the vital principle has attained non-duality, there are neither mind nor sense organs.

(164) The yogi in absorption perceives neither smell, nor taste, nor form, nor touch, nor sound, nor self, nor someone else.

(165) The yogi in absorption knows neither cold nor heat, neither sorrow nor pleasure, neither honour nor dishonour.

(166) The yogi in absorption is not troubled by death, nor bound by karma, nor troubled by disease.

(Mallinson, 2021:34)

Absorption is the goal of the practices and is in these states of trance that the yogi achieves the goal of yoga, the experience of oneness and the ability of not being affected by external stimuli (related to not feeling ‘cold or heat’).

In addition, there is an indication of AC techniques while performing postures:

(118) With his face upwards and his tongue inserted into the aperture [above the palate] the yogi should visualise [the nectar] which has been forcefully obtained from Prāṇa and dripped from the sixteen-petalled lotus †to the head†, [and his tongue] as the supreme Śakti. The yogi who drinks the stream of liquid from the surging digits of the moon becomes free from faults, with a body as supple as a lotus-stalk and lives a long time.

In the above verse Mallinson (2021) believes that the yogi is in a shoulder stand pose (called viparīta-karaṇī mudrā). This could be evidence of advanced practice of inverted postures, while concentrating the mind visualising a desired process. The process of ‘drinking the nectar obtained from prāṇa’ could represent a steady focus, a trance state that results in the benefits mentioned -free from faults, supple and that lives a long life.

ATTENTIONAL CONTROL AND THE KEY GURUS/FIGURES FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF MPY

Key MPY influencers set the foundations of practices since the early 20th century. Understanding their perspectives is therefore essential to understanding the current role of AC (and its importance in supporting wellbeing).

I start here with Kṛṣṇamācārya and continue with his disciples Iyengar and Jois. I will also consider Scaravelli, herself a student of Iyengar and Desikachar (Kṛṣṇamācārya’s son), as she is an example of radical new conceptions to the practice of yoga in the West.

All these teachers speak of the importance of concentration, emphasise the need for regular practice, breath work, and speak of an element of either devotion or belief in the practices.

TIRUMALAI KṚṢṆAMĀCĀRYA

A.G. Mohan (2010), a disciple of Kṛṣṇamācārya (1888–1989) and author of the book Kṛṣṇamācārya, attributes some of yoga’s worldwide popularity to him. White (2014) goes further stating that ‘no person on the planet has had a greater impact on contemporary yoga practice.’

Birch and Singleton (2019:4) argue that Kṛṣṇamācārya may have taken inspiration on the Hathabhyāsapaddhati, a text that describes physical postures placed in sequences.

According to Birch and Singleton (2019:55), the Hathabhyāsapaddhati did not consider philosophical aspects, and only lightly referred to gazing points. This potentially means that Kṛṣṇamācārya could have been responsible of creating a yoga that brought together a very physical practice, AC techniques, and the use of breath while moving (vinyāsa); all characteristic of MPY. Techniques of AC while in āsana such as dṛṣṭi and breath control; were largely inspired, as we can see in his Yoga Makaranda (1938), by the yoga philosophy of the Pātañjalayogaśāstra and Haṭhayoga treatises.

White (2014) points out that Kṛṣṇamācārya’s biographies heavily focus on his ‘mastery of the philosophy of the Yoga Sūtra.’ It was evident that he had the intention to fit Patañjali’s eight limbs of yoga within his methods of āsana, vinyāsa and prāṇāyāma.

Perhaps Kṛṣṇamācārya’s intention was to make his proposal more authentic and ancient, but overall, his focus was on the body through a very physical practice.

Birch and Singleton (2019:57) argue that Kṛṣṇamācārya’s Vinyāsa method, may have also been derived from Indian wrestling traditions and that the yoga he taught ‘was composite, syncretic and constantly evolving’ (2019:63).

There may have been other figures that influenced him -and his students-, such as Bhavanarao Pant Pratinidhi (1868–1951) (see Goldberg 2016) who is said to have promoted and ‘re-invented’ (Alter 2000:83) Sūrya Namaskāra (Sun Salutations) in the 1920s.

Kṛṣṇamācārya remains clear with the ancient goal of Patañjali’s yoga: to bring concentration and stillness to the mind. According to Mohan (2010:31) Kṛṣṇamācārya often said: ‘No mental control, no yoga!’.

Here there is an example of his instructions linking Vinyāsa, breath, and gazing points:

‘Make sure that the navel rests between the hands and do pūraka kumbhaka. Try to push the chest as far forward as possible, lift the face up and keep gazing at the tip of the nose. Make the effort to practise until it becomes possible to remain in this posture for fifteen minutes.’

Excerpt of the instruction of Urdvhamukhasvanāsana (Upward facing dog).

Kṛṣṇamācārya (1938:65)

In the above Kṛṣṇamācārya describes how a movement is accompanied by a specific way of breathing, a gaze to a point, and suggesting the need of regular practice to become skilful. The complexity of performance requires high levels of concentration in order to remain in posture for longer periods of time.

Referring to sirsana and sarvangāsana (headstand and shoulder stand):

‘It is said with much authority that if these two āsanas are practised regularly and properly, the practitioner will experience the awakening and rise of kundalini. Due to this, they will experience the blessings of Īśvara and will be swallowed in the sea of eternal bliss.’

Kṛṣṇamācārya (1938:146)

We could understand by the above description an ecstatic experience, characteristic of a form of religious trance.

Kṛṣṇamācārya was the teacher of B.K.S Iyengar and Pattabhi Jois who, amongst others, became responsible for spreading this mainly physical form of yoga across the world.

B.K.S. IYENGAR

In Light on Yoga, Iyengar (1966) follows Kṛṣṇamācārya’s teachings where the conquest of the Self is heavily dependent on bodily health:

The ‘body is the prime instrument of attainment…physical health is important for mental development…When the body is sick or the nervous system is affected, the mind becomes restless or dull and inert and concentration or meditation become impossible.’’ (Iyengar, 1966).

In Yoga Vṛkṣa he (1988) explores the idea of developing an ability to spread awareness of the whole body as ‘integration of the body, mind and soul’, calling this ‘meditation’ as the practitioner works on āsana. He makes contrast of this with a limited concentration on the posture or an area of the body; this performance he says in not meditation.

In addition, Iyengar (1966) teaches that a state of absorption can be achieved while doing āsana. Āsana is a ‘self-contained object of meditation’ that allows the practitioner to achieve Samādhī (see Bryant 2009).

Iyengar’s intention was to make āsana spiritual and to induce similar meditative trances as in seated meditations. Erich Schiffmann (1996), renown American teacher, describes his experience learning with Iyengar: ‘the whole point of all this physical, hard work -and it was very physical and very demanding- was to get into a deep meditative state. And for me, it worked.’

PATTABHI JOIS

In Yoga Mala, Pattabhi Jois (1999) declares that his method of Aṣṭāṅga Yoga brings the mind ‘one-pointed’; and that āsana should be practiced to improve health, to destroy illnesses, and as a ‘remedy for mental illness’.

He highlights the importance of keeping ‘faith in, and showing devotion to, the yogic limbs and the Guru’ for the practice to be effective. For him ‘faith’, can be also understood as a state of mind, the mind focuses on believing and acceptance. Furthermore, he suggests that through Vinyāsa practices such as Sūrya Namaskāra the practitioner can experience happiness and contentment.

Jois’ Aṣṭāṅga Yoga system follows Patañjali’s philosophy, but he emphasises the practice of āsana and vinyāsa as taught by his own teacher Kṛṣṇamācārya. Jois’ system involves sets of sequences of movements and postures using breath and gazing points. The addition of gazing points during the practices, according to Jois Yoga (2013) ‘facilitates dhyāna (meditation)’ but regular practice over time is needed to have results. As the practitioner becomes more skilful, he/she can progress in the sequences; these are repetitive and with time, as the practitioner has learned the sequences by heart, he/she enters of a state of light trance easily.

VANDA SCARAVELLI

Vanda Scaravelli was highly influential in the development of MPY. She promoted AC techniques based on physical sensations, changes in the body, and on keeping the mind in the present moment. These are characteristics of MPY: using stimuli-perception as the focal point to maintain concentration. She was taught by Iyengar and Desikachar, among other teachers, but created her own style focused on the spine and alignment. She was perhaps the first to include ‘fun’ as an aspect to the practice of yoga:

‘Why are we doing yoga?…We do it for the fun of it. To twist, stretch, and move around, is pleasant and enjoyable, a body holiday.’

Vanda Scaravelli (1991).

The above notion is a notable departure from the spiritual goals of salvation. Nevertheless, Scaravelli talks about spirituality and transformation through the practice of physical yoga.

‘We have to be completely present and attentive in our minds without any distractions’ (1991).

‘Do not let your mind wander during your practice, but instead be completely there…, focusing your attention on one single action, where body and brain meet at the same point at the same time.’ (1991)

She (1991) emphasises that ‘attention is energy and produces energy when we use it. It is like the battery in a car that recharges itself.’ In her view the practice of physical yoga and breath will bring the individual ‘back to that blessed state of receptivity from which we can start to learn’ (1991:86).

Her ideas help understand how yoga changed to a series of techniques to support wellbeing.

STEADINESS OF MIND AND TRANCE THROUGH ĀSANA

A western individual who sought to understand and found himself immersed in the world of Yoga, more precisely Haṭhayoga, was Theos Bernard (1950). In his book Hatha Yoga: the report of a personal experience, he describes the different practices he learned from his Indian gurus and how these were ‘directed toward the single aim of stilling the mind’ (Bernard, 1950:13). He states in his introduction: ‘There is not a single āsana that is not intended directly or indirectly to quiet the mind’ (Bernard 1950:21).

Sjoman (1999:46) gave to Bernard’s written experience paramount historical importance to understand a yoga system in practice. Āsana is described as instrument not only to calm the mind but also to build up ‘will power or determination’.

The following is Bernard’s (1950) description of a different and deeper meditative state while in sirsāsana:

‘One of the most tiring problems I encountered when building up to the higher time standards was what to do with my mind. The moment I began to feel the slightest fatigue, my mind began to wander. At this point my teacher instructed me to select a spot on a level with my eyes, when standing on my head and direct the attention of my mind to it. Shortly this became a habit, and my mind adapted itself without the least awareness of the passage of time; in fact, I was eventually able to remain on my head for an hour and longer with no more knowledge of time than when I was sleep.’

The attentional technique of gazing towards a specific point is used here to induce the experience of trance (‘no awareness of the passage of time’), and there is also an indication of recurrent practice (‘habit’) as Bernard masters his headstand practice. The effect of ‘timelessness’ appears characteristic of the experience of trance (see Tart 2000). In Modern Postural Yoga (MPY) similar instructions and effects happen as practitioners perform certain postures.

AC techniques in MPY are related largely to bodily sensations, perhaps inspired by previously discussed teachers such as Scaravelli. In contemporary yoga we need, as Nevrin (in Singleton and Byrne 2008) argues, to take into account ‘bodily experience’ particularly if we want to understand the effects of the practice.

Bodily experience and effort are precisely what Shiva Rea, arguably one of the most important influencers of the modern yoga movement called Vinyasa Flow, uses to induce trance states. A type of moving meditation called ‘Prāṇa Flow’ that, according to her, can bring ‘transformation of the body as a vehicle of divine expression’ (Rea 2014). She uses very dynamic movements based on Sun Salutations; she writes: ‘This is a kind of movement alchemy designed to awaken and transform the mover to realize the source of their meditation.’ A mind process where the practitioner diverts his/her mind from all other thought and fixates his/her mind, in this case on the action of movement to the point he/she experiences an ASC similar to a meditative trance.

THE STATE OF FLOW

A moment of full attentional absorption while practicing yoga can be considered a trance experience (Connolly 2014). In the context of MPY, this fits with the concept develop by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi called Flow. Csikszentmihalyi (1990) seems to have found another name for an ASC; but his way of describing the experience of Flow has been adopted by those speaking about an ASC induced by an activity such as sports or MPY.

Presenting his theory of flow, psychologist Csikszentmihalyi (1990) seems to speak of yoga: ‘Everything we experience – joy or pain, interest or boredom – is represented in the mind as information. If we are able to control this information, we can decide what our lives will be like’. While does not refer specifically to a yoga practice, he recognises that Eastern religions provide a guide ‘in how to achieve control over consciousness’ (Csikszentmihalyi 1990:103) and dedicates a section in his book Flow to the practice and philosophy of Yoga:

‘The similarities between Yoga and flow are extremely strong; in fact, it makes sense to think of Yoga as a very thoroughly planned flow activity. Both try to achieve a joyous, self-forgetful involvement through concentration, which in turn is made possible by a discipline of the body.’ (Csikszentmihalyi 1990).

Csikszentmihalyi (1990) suggests that individuals benefit from having a goal in order to bring ‘order in consciousness’; as his/her attention fully turns to that specific task, he/she will ‘forget everything else’ in a state of absorption.

This is similar to meditation and also can be fitted to a practitioner’s experience of MPY, where conditioned patterns of perception and behaviour are eradicated (Connolly 2014).

The musician Sting (in Gannon and Life 2002), a practitioner of Jivamukti Yoga, describes what seems a description of flow while practicing sirsāsana on a plane:

‘I feel the vibrations of the engines through the floor from my head up to my feet. It sounds like OM to the power of six thousand horses. I’m vibrating with it upside down with an inverted smile on my face. This is truly flying.

(…)

I have now been practicing yoga six days a week for ten years. And I believe that yoga has provided me with energy and focus that I would not have possessed otherwise…Yoga practice has become inextricably bound to every aspect of my life.’

Sting describes a trance experience and the positive effects of yoga on his life. Accounts as the above are easily found among many practitioners of MPY. As yoga travelled the world, meditation, philosophy, and prāṇāyāma became less important for certain groups. Singleton (2010) argues, that in the West yoga is now a synonymous of āsana. But āsana can also be transformative and bring steadiness of mind through flow experiences.

Bhavanarao, Kṛṣṇamācārya and later teachers’ recipe of combining a physical and AC practice has allowed practitioners to change their relationship with experiences by accessing ASC’s, even if they are light as moments of flow. These processes can effectively support the practitioners’ wellbeing.

Csikszentmihalyi (1990:2) argues that individuals can change their ‘inner’ experience ‘to determine the quality of their lives’, which he relates to being close to happiness, or at least moments of happiness.

CONCLUSIONS

This paper was an analysis of AC techniques as a common denominator within yoga practices throughout its history, as the inducer of ASC (from light trance to deep meditation), and yogic experiences of wellbeing. The practices themselves are varied and have evolved in time as they have been appropriated by different traditions and key figures and as I have demonstrated they involve techniques while on seated meditation or while on movement.

There were a few important marks in the yogic history of AC:

Pre-medieval: Suggestions of attentional techniques to keep the mind focused to induce meditative trance as a synonym of yoga as per in the Kaṭha Upaniṣad and Bhagavadgītā. No mention of movement, just suggestion of seated postures.

In Patañjali’s eight limb system the aim is to master the mind through the elimination of perception through concentration and breath control. No mention of movement, again just suggestions of seated postures.

Medieval: More complex goal-oriented Haṭhayoga attentional techniques to induce trance and meditative states as for example the five dhāraṇā. Here AC techniques are also introduced while on āsana such as gazing points, visualization, and breath control.

Modern: Goal-oriented attentional techniques inspired by the YS and Haṭhayoga treatises areincorporated in the practice of physical postural yoga since early 20th century. I have identified Kṛṣṇamācārya as a key figure for this incorporation.

Iyengar becomes a promoter of similar to Kṛṣṇamācārya’s yoga practices that spread to the West. The goals of yoga are increasingly focused on wellbeing and have therapeutic value. There is emphasis on physical sensations and on the present moment, gazing points and breath control, in addition to rhythmic and repetitive movement. I used Vanda Scaravelli as an example of an influencer of new techniques within MPY. The techniques no longer involve the suppression of perception but instead perception becomes the object of concentration; AC techniques infuse physical practice and induce a state of trance or flow.

After Vanda Scaravelli and other teachers of the time there is a proliferation of yoga practices in the west that combine ancient and modern practices. If there is trust in the practices, regular practice and use of breath, generally the effect is an ASC, trance or flow experience.

In the practice of MPY, there are a few elements that could help the induction of trance, group practice for example, atmosphere, and keeping the practices challenging to engage students and to keep steady concentration. Finally, another aspect that remains important from the beginning of Yoga as a set of techniques to induce trance is the use of breath. Breath is what connects mind and body, where they ‘unite’ (Wilber 1993:236).

My research demonstrates there are a few determinants needed in the practice of yoga to experience mind and body benefits from AC and trance states. Among these, the most important are: a. the belief or trust that the practices are beneficial, which may or may not be related to faith or devotion; b. constancy and discipline to practice regularly and develop skills to maintain concentration; and c. breath work enhances the effect of āsana practices and helps bringing the individual’s mind into focus.

It is clear that more research is needed to identify and classify AC techniques within yoga practice and history and to determine what forms of ASC are induced and the effects on practitioners. The understanding of the development of these techniques and their therapeutic value I argue can become key for future generations of yoga teachers and practitioners, and also could inform scholarship. As Shearer (2020:5) points out, the effects of yoga are usually an ‘extra’ that each individual discovers on their own, if the techniques were classified and introduced to yoga classes I believe practitioners would be able to access ASCs in an easier way, aware that this would be beneficial for them. In addition, this could help to trace the evolution of the practices and understanding of Yoga in contemporary times. It provides another lens through which to classify different branches of Yoga and indeed a frame to study it.

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND REFERENCES

Alter, Joseph S. 2000. Gandhi’s Body: Sex, Diet, and the Politics of Nationalism. University of Pennsylvania Press. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/soas-ebooks/detail.action?docID=3441620.

Astle, Duncan E. and Scerif Gaia. 2008. Using Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience to Study Behavioural and AC. Attention, Brain and Cognitive Development Group Department of Experimental Psychology. Published online: Wiley Periodicals. http://www.interscience.wiley.com.

Baier, Karl; Maas Philipp and Preisendanz Karin. (eds.). 2018. Yoga in Transformation: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives. Vienna: Vienna University Press.

Bernard, Theos. 1950. Hatha Yoga: The report of a personal experience. Edinburgh: Harmony Publishing.

Birch, Jason and Singleton, Mark. 2019. The Yoga of the Hathabhyāsapaddhati: Haṭhayoga on the Cusp of Modernity. Journal of Yoga Studies. Volume 2, 3-70. December 2019. ISSN 2664-1739. Available at: <https://journalofyogastudies.org/index.php/JoYS/article/view/2019.v2.Birch.Singleton.TheHathabhyasapaddhati>. Date accessed: March-June 2021.

Bourguignon, Erika. 1973. Introduction: A Framework for the Comparative Study of Altered States of Consciousness. In Religion, Altered States of Consciousness, and Social Change. Erika Bourguignon, ed. Pp. 3-35. Columbus: Ohio State UniversityPress.

Braid, James. 1850. Observations on Trance or Human Hibernation. London: John Churchill; Edinburgh: Adam and Charles Black.

Bryant, E., & Patañjali., 2009. The Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali: A new edition, translation, and commentary with insights from the traditional commentators. New York: North Point Press.

Burley, M., 2000. Hatha-Yoga: Its context, theory, and practice. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers.

Cambridge Dictionary accessed 04/05/2021 https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/trance

Castillo, R. J. 1995. Culture, Trance, and the Mind‐Brain. Anthropology of Consciousness Journal, Volume 6 (1995): 17-34.

Coombes Stephen A. et al. 2009. AC Theory: Anxiety, Emotion, and Motor Planning. J Anxiety Disorder. 2009 Dec; 23(8): 1072–1079. Published online 2009 Jul 14. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.07.009

Connolly, Peter. 2014. A Student’s Guide to the History and Philosophy of Yoga. Revised Edition. Sheffield and Bristol: Equinox Publishing.

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. 1990. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

De Michelis, E., 2014. History of Modern Yoga: Patanjali and Western Esotericism. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Eliade, Mircea. 1967. From Medicine Men to Muhammad. A source Book of the History of Religions. Part 4 of From Primitives to Zen. New York and Toronto: Harper & Row.

2009. Yoga: Immortality and freedom (1969 2nd ed. With new Introduction by David Gordon White). Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Feuerstein, Georg. 2013. The Psychology of Yoga: Integrating Eastern and Western Approaches for Understanding the Mind. Boulder: Shambala Publications.

2003. The Deeper Dimension of Yoga. Theory and Practice. Boulder: Shambhala Publications.

2008. The Yoga Tradition: Its History, Literature, Philosophy and Practice. Prescott: Hohm Press.

1989. The Yoga-Sutra of Patanjali. A New Translation and Commentary. Rochester: Inner Traditions International.

1989b. Yoga: The Technology of Ecstasy. Los Angeles: Tarcher.

Flaherty, Mary. 2020. Does Yoga Work? Answers from Science. Student Edition. Self-Publication. Great Britain: Amazon.

Forrest, Ana T. 2011. Fierce Medicine: Breakthrough practices to heal the body and ignite the spirit. New York: HarperCollins.

Gannon, Sharon and Life, David. 2002. Jivamukti Yoga. New York and Toronto: Random House Publishing Group.

Garbe Richard. 1900. The Monist on the Voluntary Trance of Indian Fakirs. The Monist, July, 1900, Vol. 10, No. 4 (July, 1900), pp. 481-500. Oxford University Press

Gharote, M. L., Devnath Parimal and Kant Jha Vijay. 2019. Haṭharatnāvalī: A treatise on Haṭhayoga of Śrīnivāsayogī. 5th Reprint 2019 of the First Edition 2002. Lonavla: The Lonavla Institute.

Goldberg, Elliot. 2016. The path of modern yoga: The history of an embodied spiritual practice. Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions.

Gupta, A., and J. Ferguson 1997. Discipline and Practice: ‘The Field’ as Site, Method and Location in Anthropology. In A. Gupta and J. Ferguson (eds) Anthropological Locations: Boundaries and Grounds of a Field Science, pp.1-46. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Halbfass, W. 1992. Tradition and Reflection: Explorations in Indian Thought. Delhi: Sri Satguru Publications.

Harrington, Anne. 2016. Thinking about Trance Over a Century: The Making of a Set of Impasses. In Hypnosis and meditation: Towards an integrative science of conscious planes, eds. Michael Lifshitz and Amir Raz. New York: Oxford University Press.

Inglis, Brian. 1990. Trance: A Natural History of Altered States of Mind. London: Paladin.

Iyengar, B.K.S. 1966. Light on Yoga. Yoga Dipika. Revised edition 1979. New York: Schocken Books.

1988. Yoga Vṛkṣa. The Tree of Yoga. Oxford: Fine Line.

Jois, K. Pattabhi. 1999. Yoga Mala. The original Teachings of Aṣṭāṅga Yoga Master Sri K. Pattabhi Jois. New York: North Point Press.

Jois Yoga. 2013. An Introduction to the Fundamentals of Aṣṭāṅga Yoga Published by Jois Yoga http://lightonAṣṭāṅgayoga.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/jois_book_4.15.pdf. Accessed 01/07/2021.

Kṛṣṇamācārya, Sri T. 1938. Yoga Makaranda or Yoga Saram (The Essence of Yoga). First Part. Tamil Edition. Translated by Ranganathan Lakshmi and Ranganathan Nandini. 2006. Kannada: Madurai C.M.V. Press.

Larson, G. J. 2017. Classical Sāṃkhya: An Interpretation of its History and Meaning (6th edition.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Maas, Philipp A. 2009. The So-Called Yoga of Suppression in the Pātañjala Yogaśāstra. Eli Franco (ed.) in collaboration with Dagmar Eigner, Yogic Perception, Meditation, and Altered States of Consciousness. Sitzungsberichte der phil.-hist. Klasse 794 = Beiträge zur Kultur- und Geistesgeschichte Asiens 64. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (2009): 263–282. Print.

Malbon, Ben. 1999. Clubbing: Dancing, Ecstasy, Vitality. Taylor & Francis Group, 1999. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/soas-ebooks/detail.action?docID=180058.

Mallinson, James. 2021. Vivekamārtaṇḍa, ed. James Mallinson. Forthcoming in the Haṭha Yoga Series of the Collection Indologie of the Institut Français de Pondichéry/École française d’Extrême-Orient, Pondicherry.

2007. The Khecarīvidyā of Ādinātha: A Critical Edition and Annotated Translation of An Early text of Haṭhayoga. London: Routledge.

2004. The Gheranda Samhita: The original Sanskrit and an English translation. Woodstock, N. Y.: YogaVidya.com.

Mallinson, James, & Singleton, Mark. 2017. Roots of Yoga. Milton Keynes: Penguin Books.

Mason, Heather and Birch, Kelly. 2018. Yoga for Mental Health. Glasgow: Handspring Publishing.

Mindful Nation UK. 2015. Report by the Mindfulness All-party Parliamentary Group (MAPPG) – Oct 2015, 5–15.

Mohan, A. G. 2010. Kṛṣṇamācārya: His Life and Teachings. Boston and London: Shambhala.

Newcombe, Suzanne and O’Brien-Kop, Karen eds. 2021. Routledge Handbook of Yoga and Meditation Studies. London: Routledge.

2019. Yoga in Britain: Stretching spirituality and educating yogis. Sheffield, South Yorkshire; Bristol, CT: Equinox Publishing Ltd.

Patrick Olivelle. 1996. The Early Upanishads: Annotated Text & Translation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Patton, L. L. 2008. The Bhagavad Gita. London; New York: Penguin.

Prabhu, H. R. Aravinda and Bhat, P. S. 2013. Mind and consciousness in yoga – Vedanta: A comparative analysis with western psychological concepts. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013 Jan; 55(Suppl 2): S182–S186. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.105524. Accessed on 16/03/2021 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC370five680/

Rea, Shiva. 2014. Tending the Heart Fore. Living in the Flow with the Pulse of Life. Boulder: Sounds True.

Roy, Ranju and Charlton, David. 2019. Embodying the Yoga Sūtra: Support, Direction, Space. London: Pinter & Martin.

Sarbacker, Stuart Ray. 2021. Tracing the Path of Yoga. The History and Philosophy of Indian Mind-Body Discipline. New York: Suny Press.

Shaara, Lila, and Strathern, Andrew. 1992. A Preliminary Analysis of the Relationship between Altered States of Consciousness, Healing, and Social Structure. American Anthropologist, vol. 94, no. 1, 1992, pp. 145–160. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/680042. Accessed 30 June 2021.

Shearer, Alistair. 2020. The Story of Yoga: From Ancient India to the Modern West. London: Hurst & Company.

Scaravelli, Vanda. 1991. Awakening the Spine. Stress-free yoga for health, vitality and energy. First ed.: London: Harper Collins Publishers. Reprinted 2017. London: Pinter & Martin.

Schiffmann, Erich. 1996. Yoga: The Spirit and Practice of Moving into Stillness. New York: Pocket Books.

Simpson, Daniel. 2121. The Truth of Yoga: A Comprehensive Guide to Yoga’s History, Texts, Philosophy, and Practices. New York: North Point Press.

Singleton, M., & Byrne, J., 2008. Yoga in the modern world: Contemporary Perspectives. London; New York: Routledge.

Singleton, Mark. 2010. Yoga Body: The Origins of Modern Posture Practice. New York: Oxford University Press.

Śivānanda.1935. Mind. Its Mysteries & Control. Uttarakhand: The Divine Life Trust Society. Twentieth Edition 2020.

1945. Concentration and Meditation. Uttarakhand: The Divine Life Society. Sixteenth Edition. 2017.

Sjoman, N. E. 1999. The Yoga tradition of the Mysore Palace (2nd ed.). New Delhi: Abhinav Publications.

Swami Niranjanananda Saraswati. 2003 [1993]. Dharana Darshan: Yogic, Tantric and Upanishadic Practices of Concentration and Vizualization. Reprinted 1999 Bihar School of Yoga Second Edition.New Delhi: Thomson Press.

Tart, Charles T. 2000. States of Consciousness. Reprint of 1983 edition. Lincoln: Backingprint.com.

Tola, Fernando and Dragonetti, Carmen. 1987. The Yogasutras of Patanjali. On Concentration of Mind. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers.

Vecera Shaun P., Cosman Joshua D., Vatterott Daniel B., and Roper Zachary J.J. 2014. Chapter Eight – The Control of Visual Attention: Toward a Unified Account, Editor(s): Brian H. Ross, Psychology of Learning and Motivation. Academic Press, Volume 60, 2014, Pages 303-347, ISSN 0079-7421, ISBN 9780128000908, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-800090-8.00008-1.

White, David Gordon. 2014. The Yoga Sutra of Patanjali. A Biography. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Wilber, Ken. 1993. The Spectrum of Consciousness. 2nd Ed. (1st 1977). Wheaton: Quest Books.

Wittman, Marc. 2015. Altered States of Consciousness: Experiences Out of Time and Self. Translation by Hurd, Philippa. 2018. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

[1] See for example Flaherty (2020) that presents several research studies on yoga benefits.

[2] Using Elizabeth De Michelis (2014) terminology.

[3] ‘Attentional Control’ is broadly used as a synonym of Concentration in Psychology.

[4] Scholars such as Tart (2000) discuss Altered States of Consciousness without using the word trance. In this paper I use the terms mostly as synonyms, although it would be appropriate to mention that there are a few ASCs that are not trance states such as for example sleeping.

In hatha yoga, ha means prana or the sun and tha, the mind or the moon; hatha meaning the union of the pranic and mental forces, a duality that exists in everything (Muktibodhananda 1998). In the context of the HYP, and as explained by Swami Satyananda Saraswati, Hatha Yoga is the collection of practises that prepares oneself for meditation. Meditation has the purpose of purifying the mind, but before being able to do this, according to the HYP, the first action is to work the body, calm the mind and balance the flow of energy or prana through asana and pranayama, and purify the whole body with the shatkarmas: the stomach, intestines, nervous system and other systems.

In hatha yoga, ha means prana or the sun and tha, the mind or the moon; hatha meaning the union of the pranic and mental forces, a duality that exists in everything (Muktibodhananda 1998). In the context of the HYP, and as explained by Swami Satyananda Saraswati, Hatha Yoga is the collection of practises that prepares oneself for meditation. Meditation has the purpose of purifying the mind, but before being able to do this, according to the HYP, the first action is to work the body, calm the mind and balance the flow of energy or prana through asana and pranayama, and purify the whole body with the shatkarmas: the stomach, intestines, nervous system and other systems.